On Nov. 21, barely more than one month from now, the U.S. men’s national team will play their first World Cup game in almost 8½ years. Thank goodness. More than 1,600 days passed between when the Americans were eliminated from World Cup qualification in 2018 and when they clinched this time around, and now more than 200 days have passed since qualification. After the longest wait ever between World Cups, it’s just about here. Ready or not.

National team coaches are signed with World Cup cycles in mind, and U.S. manager Gregg Berhalter’s contract is scheduled to end in the weeks after the tournament in Qatar. His first year was spent fiddling with lineups and getting looks at as many players as possible, and his second was almost nonexistent due to COVID stoppages. His third was a roller coaster of injuries, a trio of wins over Mexico and a bumpy and frustrating early crawl through qualification. His fourth included qualification and a summer (and early fall) of listlessness.

Optimism has waxed and waned, as has faith in the job Berhalter is doing. But as we enter the valedictory stage of this eight-year drought, here are four questions I still have about Berhalter, his team and the massive tournament ahead.

How have the U.S. done under Berhalter?

To start answering that question, let’s step back and answer a broader question: How have the U.S. done, period?

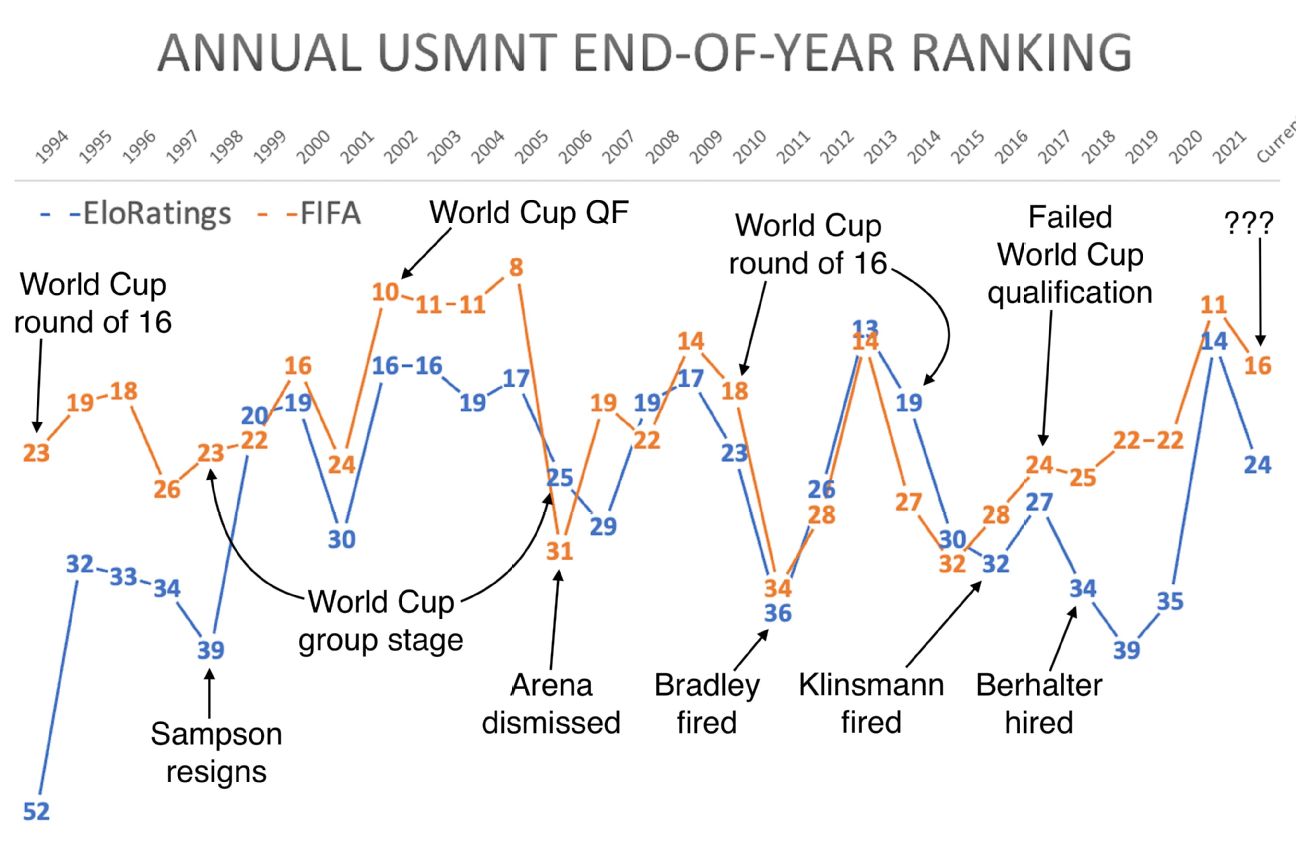

The national team is currently 16th in the FIFA rankings and 24th in the more predictive ratings at EloRatings.net. Here’s a quick chart of how that compares to its year-end rankings going back to 1994, the year the U.S. hosted the World Cup.

Considering the country’s interest in soccer has grown, and considering its investment in soccer has grown — perhaps most notably through the increased investment in MLS academies and leagues below MLS — the U.S. hasn’t really improved its overall standing in world soccer since its initial post-1994 surge. Its golden era in both sets of ratings began in about 2000, picked up steam in 2002 and petered out around 2005. Since then, the U.S. has been immersed in almost identical cycles.

The U.S. averaged a year-end ranking of 13th in the two ratings above in 2005, but they had fallen to an average of 28th the next year, when Bruce Arena’s managerial contract was allowed to expire. Three years later, in 2009, they were back to an average of 16th under Bob Bradley, but they had fallen to an average of 35th two years when he was fired in 2011.

These cycles continued under Jurgen Klinsmann: They were back to within sniffing distance of the top 10 in 2013 but had fallen back into the 30s when he was fired in 2016. And after a couple of stagnant years at the start of the Berhalter era — thanks in part to a lack of opportunities during the COVID year of 2020 — they had surged right back to the high teens in 2021 before slipping to a current average of 20th.

We head into the World Cup, then, at a massive pivot point. A solid showing at the World Cup* would likely bump the U.S. back up and mark the first time since 2004-05 that they averaged a ranking in the teens at the end of two consecutive years. With so much of the core roster still years from reaching its peak, this would paint an awfully optimistic picture of the years ahead.

*How would we define a “solid” showing, by the way? Considering that EloRatings.net rates the U.S. (24th), Iran (21st) and Wales (26th) almost equally at the moment, “solid” would probably require advancement to the knockout rounds and the avoidance of a blowout against England and/or a round-of-16 opponent.

A lesser showing in Qatar, meanwhile, would mean that the Berhalter era’s trajectory would mirror that of both the Klinsmann and Bradley eras in a lot of ways.

So let’s go back to the original question: How has Berhalter done thus far? The same as just about any recent U.S. coach, it appears. But based on how Americans have been performing at the club level, one could make the case that he’s achieved approximately the same results with a more talented, if less experienced, squad. When the U.S. reached the World Cup quarterfinals, they did so with a squad featuring seven players who were playing for a team in one of Europe’s big five leagues. This year’s World Cup squad will have 12-14 such players.

– What we learned about Pulisic from his new book

Granted, some of the team’s most talented players have struggled with injury; here’s where I once again note that Christian Pulisic, Giovanni Reyna, Weston McKennie, Tyler Adams and Sergino Dest have played together in the same U.S. match just once — ever. But with greater depth of options, a three-and-out appearance at the World Cup — especially with what might actually be a reasonably healthy squad — would still reflect poorly on Berhalter’s overall performance.

Is it fair that after four years and 56 matches in charge, Berhalter will be evaluated almost entirely by a three- to five-match swing at the end of the fourth year? Almost certainly. Is that way it works in international soccer? Absolutely. Put another way, the World Cup is the final exam at the end of the semester.

Who gets the final eight (or so) spots?

You’re allowed to take 26 players to Qatar. Based on who’s currently healthy and who Berhalter has seemingly preferred over the past year or so, we can safely guess about 18 of those names (listed alphabetically by position).

Berhalter could spring a surprise based on club form — which could negatively impact someone like de la Torre, who has played just 38 minutes for Celta Vigo this season, or Dest, who’s struggled since moving to Milan from Barcelona over the summer — but it would indeed be a surprise.

Unless Long’s iffy performances in September friendlies have given him pause, Berhalter has made his preferences pretty clear at this point. And aside from center-back Miles Robinson, whose unfortunate Achilles injury in May eliminated him from consideration after he had all but locked a starting spot for the U.S., it appears that despite a run of recent minor injuries, all of his other first-choice players would be currently available if the World Cup began today. (Knock on wood, or perform your necessary jinx-prevention exercises here.)

So that leaves eight other players to select: a third goalkeeper, plus probably either one or two players in each of the other position categories above. Based once again on who Berhalter has seemingly taken the hardest look at over the past year or so, here are approximate lists of likely candidates for those final spots.

Since the start of 2021, these are the only two other keepers to play for Berhalter besides Turner and Steffen.

Palmer-Brown and McKenzie took part in the last international window, and Carter-Vickers would have if not for injury. Sands has played six times for the U.S. since the start of 2021 and is doing well for Rangers. John Brooks has also played six times for Berhalter in that span, but seems to be on the outs and has not seen much playing time since signing with Benfica.

This unit is a bit of a mystery. Robinson, Yedlin and probably Dest are probably no-brainers, but at least one more fullback will go to Qatar. Cannon is a Berhalter favorite, but is still working his way back from a groin injury that knocked him out of September friendlies. Scally is 19 and already in his second season starting for a Bundesliga squad; he would seem like a no-brainer, but Berhalter has played him only three times.

With Roldan also battling a groin injury (he’s healthy now), Berhalter was able to give longer looks to Cardoso and Tillman, both of whom have made four appearances for the U.S., in September’s international window. Busio seemed on his way to locking up a spot a year ago, but has made only one appearance in the last 13 U.S. matches.

Here’s where Berhalter’s preferences have particularly run counter to form and stats. He invited Pepi to September camp despite a long run of poor form, and in 59 minutes against Saudi Arabia, Pepi managed just 13 touches and no shots. He also invited Sargent at the 22-year-old’s first sign of improved form in the English second tier; Sargent played 45 minutes against Saudi Arabia with 15 touches and no shots. Shooting tends to be an important characteristic for a forward and outside of Ferreira, Berhalter has struggled to find someone who consistently attempts them.

– Bonagura: Projecting the USMNT roster

It would surprise no one if Berhalter selected two or so from a pool of Pepi, Sargent and veterans Arriola and Morris. They are clearly who he’s most comfortable with at this point, for better or worse. But if club form actually matters, then Pefok or Wright should be garnering longer looks than they have received of late.

Pefok has scored three goals with four assists in nine matches for Bundesliga-leading Union Berlin; he might not naturally provide the link-up play Berhalter wants from his center-forwards, but he is part of what might be the best counter-attacking unit in Europe at the moment, and it seems that might be a good asset to have on your bench, at the very least. Wright, meanwhile, has scored seven goals in nine Turkish Super Lig matches after scoring 14 last season, but he’s seen only 119 minutes in a U.S. shirt.

While we’re talking about in-form scorers, one would have also thought the 24-year old Brandon Vazquez would have gotten a longer look by now. Vazquez scored 19 goals during FC Cincinnati’s dramatic rise in MLS this season, but Berhalter has yet to give him an appearance. (He isn’t cap-tied and is also eligible to play for Mexico.)

Berhalter talks a lot about wanting to choose the right team instead of what might simply be the most talented team. That can make obvious sense, but only if you’re not sacrificing quality in service of an identity that hasn’t necessarily taken hold after four years.

0:58

Rob Dawson feels Pep Guardiola managing USMNT in a World Cup when he leaves Manchester City is a particularly intriguing prospect.

Does the team’s identity fit the personnel?

On Dec. 4, 2018, in the news conference introducing Berhalter as head coach, Earnie Stewart, a former USMNT striker and its current sporting director, was asked how success should be defined for the Berhalter era. He broke his answer into three parts. Two were pretty concrete — qualifying for the 2022 World Cup and succeeding there — but the third was more abstract: “Making sure that the way we play [is] identified through our fans, so that what they see on the field is what they want to see.”

That answer was problematic from the start, if only because fans are never going to agree 100% on aesthetics. But when you hire Berhalter, you’re hiring possession.

In his five seasons with MLS’ Columbus Crew, Berhalter’s teams averaged at least 5.0 passes per possession every year and managed at least a 53.6% possession rate in three of those five. Columbus was more passive in defense than a lot of possession teams, but he clearly believed in patient building from the back and attempting to slowly pin opponents deep with longer possessions.

It was easy to see how it might be difficult to piece together such a concrete style for an international team when you’ve only got so much practice time and you have no control over who’s in your player pool. Would the U.S. be able to adhere to this approach against more talented teams considering talent and possession correlate pretty well with each other? And would short passing work without pratfalls on some of the bumpier pitches they might encounter in CONCACAF road play?

When asked about this in his introductory news conference, Berhalter simply said, “I think when I took over in Columbus five years ago, if I would tell you the look of Columbus was going to be a possession-based team, you’d probably be asking similar questions.” That is to say, he didn’t answer the question at all.

Four years in, building a possession style has indeed turned out to be difficult. The U.S. has been able to dominate possession and win big over teams with far lesser talent: In 56 total matches, they have averaged 57% possession and gone over 65% on 10 occasions. But when facing good teams, they have either struggled to control the ball or struggled to create anything with it.

In 26 matches Berhalter’s U.S. have played against teams that are in this year’s World Cup, they enjoyed more possession 17 times, but they scored just 16 goals in those matches and averaged 1.53 points per game. In just nine matches under 50%, they scored nearly as many goals (13) and averaged 1.89 points per game. Most of their best performances — 4-1 over Canada in November 2019 (37% possession), 3-0 over Morocco in June 2022 (52%), all three 2021 wins over Mexico (37%, 43% and 49%) — came without loads of possession. They were both better and more prolific without the ball, despite Berhalter’s intentions.

It was the same story throughout World Cup qualification. In five matches at 50% possession or lower, they averaged 2.2 points and 2.2 goals per game. In nine matches over 50% possession, they averaged 1.6 points and 1.1 goals. Establishing quality possession has been hit-or-miss and when they do it, they have not found the creativity to unlock packed-in defenses. It is absolutely true, though, that better injury luck would help: Pulisic, Reyna and Weah all play for possession-heavy club teams, but they’ve only played together three times.

Even worse: In their September friendly against the U.S., Japan pressed them heavily and the U.S. caved. Japan isn’t a team forever reliant on pressing, but they sensed weakness and took full advantage. They began an incredible 15.2% of their possessions in the attacking third — for comparison, even Manchester City (10.7%) and Bayern Munich (10.6%) are nowhere close to that percentage in club play.

1:32

Matt Turner speaks about his USMNT teammates and explains why he doesn’t like the golden generation phrase.

Against both Japan and Saudi Arabia, the U.S. enjoyed at least 55% possession, but managed just 11 combined shot attempts, two shots on goal and zero goals. In their last World Cup tuneups, after almost four years under Berhalter, the U.S. failed miserably in most of what were supposed to be their core tenets.

To be sure, a disappointing tuneup game can help refocus everyone and get motivation levels to where they need to be; the U.S. lost to Netherlands and Ireland in the run-up to the 2002 World Cup, after all, only to nearly reach the semifinals. All hope is obviously not lost, but the fact that the performances were both poor and seemingly indicative of previous issues was awfully scary and definitely not what fans “want to see.”

Who wins: the USMNT or the Snubbed USMNT?

Let’s finish this piece with a thought exercise: If I’m so concerned about the U.S. not playing a style that their talent base is built to play, can I craft an “Alternate USMNT” that could potentially beat the actual USMNT that Berhalter is likely to put on the field in Qatar? Better yet, can I do it without using any of Berhalter’s regulars?

Choosing only from players who have seen no more than 150 minutes with the national team over the last 12 months, here’s my 26-man roster. Because of solid depth at center-back and iffy depth at fullback, we’re going with a Union Berlin-esque 3-5-2 with veteran structure in defense and as much speed as possible up the pitch.

-

Goalkeepers: Sean Johnson (NYCFC), Ethan Horvath (Luton Town) and Josh Cohen (Maccabi Haifa)

-

Center-backs: Erik Palmer-Brown (Troyes), Tim Ream (Fulham), James Sands (Rangers), Auston Trusty (Birmingham City), John Brooks (Benfica), Matt Miazga (Cincinnati)

-

Fullbacks: Sam Vines (Royal Antwerp), Cristian Roldan (Seattle Sounders), DeJuan Jones (New England), Konrad de la Fuente (Olympiacos), John Tolkin (New York Red Bulls)

-

Midfielders: Djordje Mihailovic (CF Montreal), Malik Tillman (Rangers), Sebastian Lletget (Dallas), Kevin Paredes (Wolfsburg), Gianluca Busio (Venezia), Alan Sonora (Independiente), Michael Bradley (Toronto), Julian Green (Greuther Furth)

-

Forwards: Jordan Pefok (Union Berlin), Haji Wright (Antalyaspor), Brandon Vazquez (FC Cincinnati), Josh Sargent (Norwich City)

To be sure, the player pool is thin when it comes to perfect wingback options — though Vines and perhaps Jones could thrive in such roles — and the real U.S. midfield of Adams, McKennie and Musah offers far more athleticism and upside than my selection. But it’s possible that this team is equal to the actual USMNT at the front and back and, with the mix of creativity in midfield and pure speed and finishing ability up front, it could adhere to its chosen identity better than the actual USMNT have of late.

The real USMNT would be favored to win against this snubbed team, and hopefully they would win indeed. But if Berhalter’s team indeed fails to advance in Qatar, despite what might be the nation’s richest overall talent pool to date, it will likely be because other teams know themselves and play to their strengths better than the U.S. do. And that would not reflect well on the four-year Berhalter era.